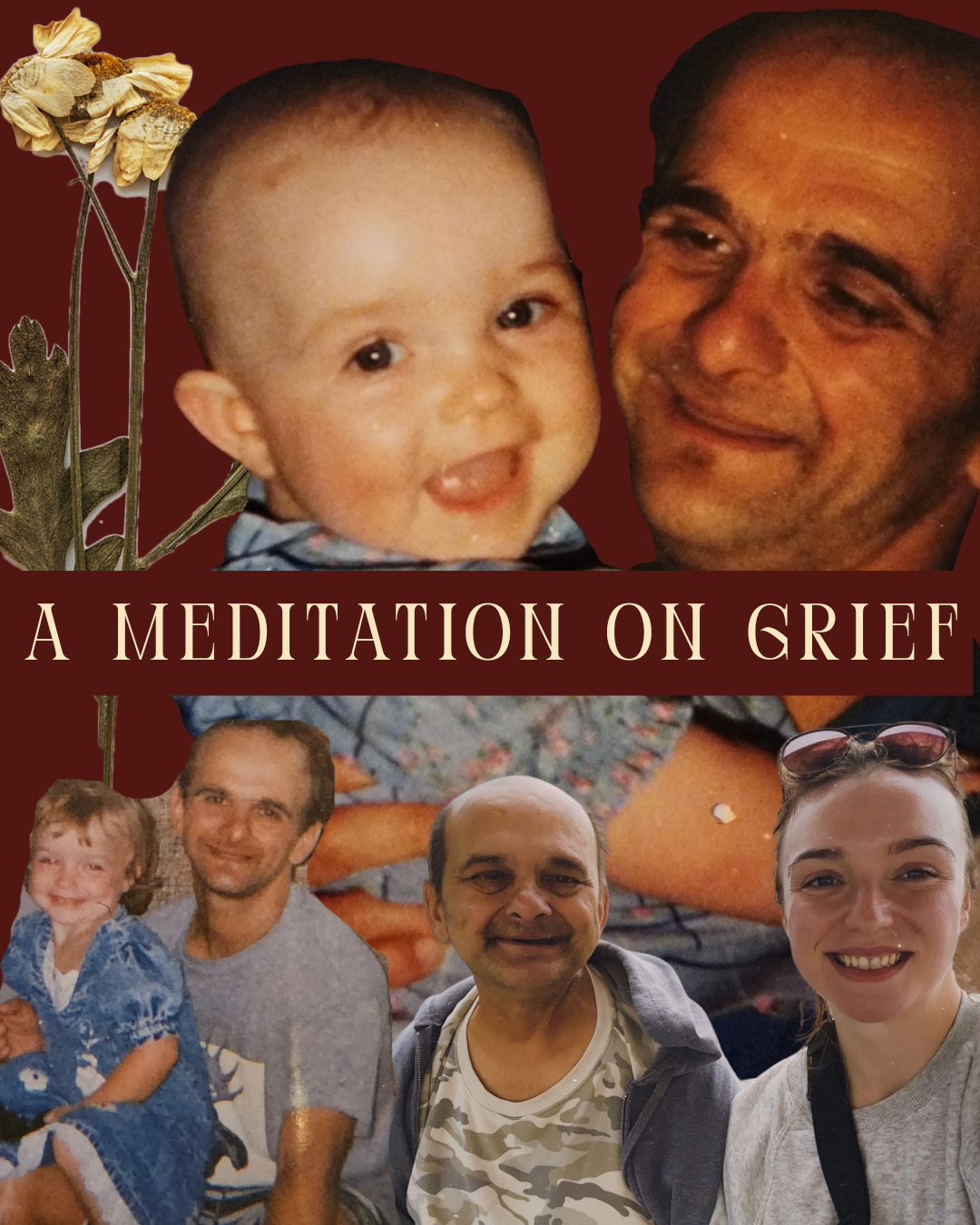

Finding the Voice Through Embodiment

Before we ever had language, we had tone. Before grammar, there was rhythm. Before we spoke, we sang.

When did this start?

It may sound poetic, but it’s also backed by science: research in evolutionary anthropology and neuroscience increasingly supports the idea that vocal expression through melody and rhythm predates spoken language. Some scholars refer to this as “musilanguage”; a pre-linguistic, musical form of communication rooted in emotional expression and social bonding. In fact, neuroscientist Aniruddh Patel and others have argued that singing likely evolved as a foundational layer upon which language was later built. Our ancestors likely cooed, wailed, and groaned to connect, long before they structured thoughts into sentences.

This isn’t just trivia. It’s a profound reminder that the human voice is inherently musical. Expression through sound is native to us, not a learned trick. And yet, in modern voice education, we often start at the level of technique: laryngeal mechanics, breath control, resonance mapping. These tools are, of course, useful; essential, even, but they don’t always help someone feel their voice.

Embodiment Through Voice Work

As a voice coach, I’ve seen this a lot: you can show someone where the diaphragm is, describe how the soft palate lifts, even draw diagrams of the vocal tract, and still, the voice stays trapped.

That’s because understanding where a sound happens doesn’t guarantee you’ll be able to make it. The body isn't a machine! It’s a living archive. It stores feeling, tension, memory, protection, pleasure. The voice responds to all of this. And sometimes, it refuses to be summoned through explanation alone.

So I began working differently. Less with mechanics, more with meaning.

What if we called the voice instead of chasing it?

What if we let the body lead?

In Voice Work sessions, I might ask:

- “What’s the sound of grief that didn’t get to finish?”

- “Can you let your voice shake like a held-in laugh?”

- “Where in your body is a ‘yes’ trying to break out?”

These prompts may not reference anatomy directly, but they often create a faster and more profound result because they’re rooted in lived experience. They’re rooted in the felt sense of the body, which is often far more accessible than abstract technique.

The Body Remembers, and So Does the Voice

This is where embodiment comes in. When someone tunes into their body and gives it permission to feel, sound naturally follows suit.

Sometimes it’s raw, messy, and unpolished, but it’s real. Once that authenticity is accessed, then we can introduce tools to refine, support, and grow it. In this way, technique becomes more of a frame and less of a cage.

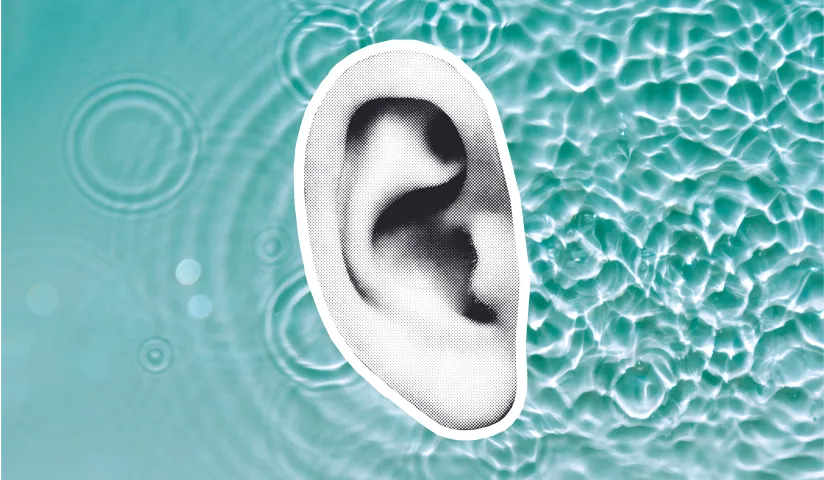

There’s also a neurological basis for all of this. The vagus nerve (a key player in our parasympathetic nervous system) plays a central role in vocal function and emotional regulation. It runs from the brainstem down through the throat, heart, lungs, and into the gut, helping to regulate breath, heart rate, digestion, and vocal tone.

There’s a lot of buzz around “vagus nerve stimulation” these days in wellness circles, and while not all of it is backed by rigorous evidence, here’s what is supported by science:

Activities like singing, humming, and slow vocal toning can stimulate the vagus nerve through what's known as the auricular branch and laryngeal branch.

This kind of stimulation has been shown to promote relaxation and even support your mood. It’s one reason many people feel emotionally moved or deeply calm after vocalizing or being immersed in sound.

When we vocalize with awareness and not just for pitch or performance, but from a place of inner connection, we’re also engaging with our nervous system. We’re not just “making sound,” we’re creating shifts in state. We’re re-patterning safety. We’re communicating, even to ourselves, that we’re allowed to take up space.

We are wired for sound.

We are wired for song.

And that wiring runs through the entire body, not just the brain.

In this light, vocalization becomes more than singing or speaking. It becomes a process of remembering. Re-inhabiting the self. Letting go of the performance of being “good” and reclaiming the birthright of being resonant and loud.

This is the heart of Voice Work: not just teaching people how to sound better, but how to feel more like themselves when they do.

So if your voice feels stuck, don’t just look for it in your throat.

Look for it in your memories. In your gut. In the places you’ve learned to stay silent.

Your voice is not lost. It’s waiting to be felt.

SOURCES:

1. Humming / Bhramari Pranayama and nervous system regulation

A study comparing humming with other activities (like physical exertion, emotional stress, and sleep) found that humming yielded the lowest stress index, with measurable benefits to heart rate, heart rate variability (HRV), and subjective calm. It supports the idea that gentle vocalization such as humming can reliably stimulate the parasympathetic system and by extension, vagal activity.

2. Expert clinician commentary from The Washington Post

An article published March 30, 2025, outlines how voice practices like humming, chanting, singing, or gargling activate the recurrent laryngeal branch of the vagus nerve and can promote rest, digestion, and emotional balance. It references dozens of researchers and aligns with polyvagal-informed hypotheses, while noting that the broader theory remains under debate.

Book in your Voice Work sessions at www.emgodin.com/voice-work